We Got Local, But Forgot Scale

The work of entrepreneur support is widely considered a localized endeavor. We talk a lot about building local stakeholder networks, and we should. Every founder’s context is real, and every community’s constraints are real. But in smaller markets, that same virtue can quietly trap us: it limits sustainability for the organizations doing the work, and it limits connectivity for the entrepreneurs we serve.

It’s worth asking the uncomfortable question: does our commitment to “local-first” sometimes inhibit the growth of our startups?

Over the last two years, we’ve been able to partner with Moonshot on a number of initiatives, and I’ve been consistently impressed by their approach to scale in supporting entrepreneurs. I recently sat down with their CEO, Scott Hathcock, to learn how Moonshot has evolved over the last decade and how they think about serving rural and midsize communities at scale.

Scott’s story starts with a hard truth that many ESOs recognize instantly: you can do great work for years and still be invisible to the very community you serve. The organization he inherited, NACET (Northern Arizona Center for Entrepreneurship and Technology) had been around for 15 or 16 years, yet “people didn’t know how to say it. People didn’t know what it stood for.” In a town of about 70,000, that kind of brand confusion is not a marketing problem. It’s a gravity problem. If your work cannot be named, it cannot be repeated, shared, sponsored, or scaled.

Scott didn’t treat naming as decoration. He treated it as infrastructure.

He wanted what he called a “hero image,” and more than that, a story that could act like a decision matrix for everything that followed. He connected Moonshot back to Flagstaff’s role in space science and NASA training, then to Kennedy’s public declaration about going to the moon, and then to what it means when an entrepreneur publicly declares the future they intend to build.

That is the first “node” concept hiding in plain sight. A declaration attracts problem-solvers. A story attracts collaborators. A shared narrative attracts capital.

But a story’s ability to attract capital is wasted if the organization lacks the infrastructure to turn that capital into a sustainable, compounding asset. To keep the lights on and scale the mission, we must also focus on the financial model.. And this is where Scott’s perspective cuts through the polite optimism our field sometimes defaults to.

He describes entrepreneur support as fundamentally aspirational: “At the end of the day, we are a marketing company… we’re selling the idea of you achieving greatness.” Yet the industry’s legacy financial model often expects ESOs to operate like a civic utility, funded like a line item, measured like a feel-good program, and renewed like a political favor.

That model breaks hardest in rural communities.

As Moonshot’s early incubator contracts got closer to ending, Scott made a deliberate decision: “Let’s not do those legacy incubator contracts anymore. Let’s look at a model that we can provide smaller communities the same access, without the same cost of the traditional model.”

He doesn’t mince words about what that “traditional model” costs. “Their average [is] 250 to $350,000 a year… boots on the ground, facilities and instructors.” That number alone eliminates most small towns before the conversation even starts.

So Moonshot started building toward a different number. “We’re close with a $25,000 model… that assists communities, smaller communities,” leveraging delivery that can happen online to scale the efforts of local stakeholders, by connecting them and increasing visibility.

Here’s the strategic move that matters: Scott isn’t trying to win an argument about whether local matters. He agrees local matters. He’s trying to make local survivable.

Because if local support is not survivable, it becomes episodic. If it becomes episodic, founders lose continuity. And when founders lose continuity, they lose momentum, access, and eventually, belief.

This is where our partnership enters the story, and it’s also where Scott’s thinking shifts from “program” to “system.”

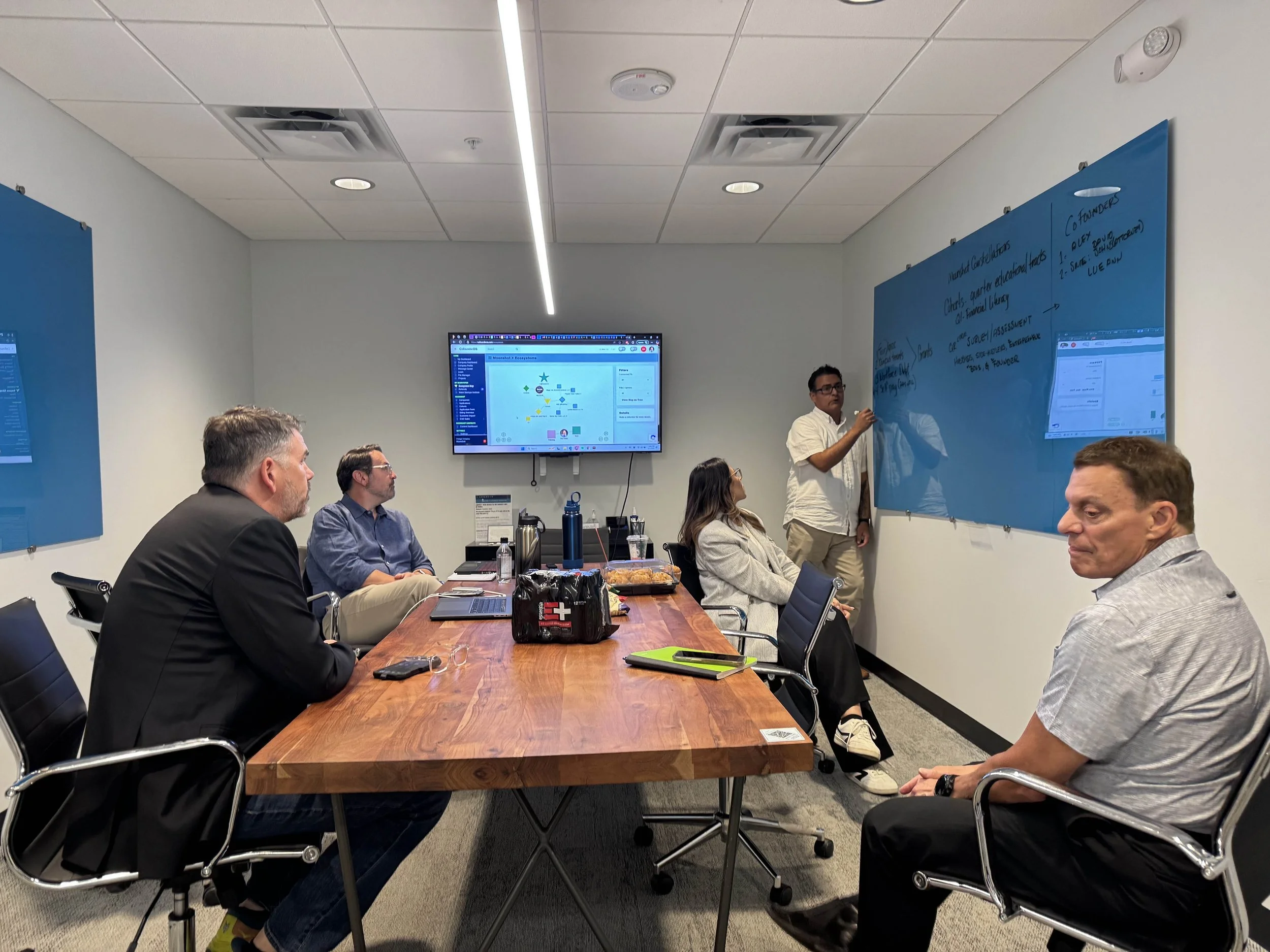

“The biggest change we’ve made recently is partnering with Make Startups and CofounderOS,” he told me. Not because software is shiny, but because data changes the economics of credibility. “That platform provides us with the data that shows when we work with individuals, I can now correlate that company to economic development within that small community,” Scott said.

Then he draws a bright line that every funder, board member, and city manager understands: “That right there is a game changer, because we can make the case. We can make the ROI. It’s not just a feel good story. It’s a data driven story as well as a feel good story.”

That sentence is a wedge in the legacy financial model.

When support is only “local,” it often stays informal, relationship-based, and hard to measure. That is good for trust, but bad for sustainability. When support becomes measurable, it becomes financeable. When it becomes financeable, you can stop begging for one-off generosity and start building recurring participation.

Scott’s next move is the part that ESOs should be paying very close attention to, because it reframes the entire rural ecosystem challenge.

He has a three-year window to prove the model with public funding, then he wants to go back to communities with evidence: “Look what we’ve done… here’s the true numbers.” And then he wants a small, practical buy-in that a town can actually say yes to: “How about you pay for five seats… and then we could have a cafeteria list that then scales that number up.”

That’s it: Five seats.

That is not a grant. That is not a contract for a building. That is not a fragile political commitment. It is a licensing model for access into a larger system.

This is “#BeTheNode” in operational form.

A small community does not need to build the whole machine. It needs the ability to plug into a machine that already works, on terms it can afford, with proof it can defend. When multiple towns buy in at a small level, the network becomes the asset. When the network becomes the asset, founders gain something local-only support can rarely provide: continuity across geography, connectivity to broader markets, and a shared infrastructure that compounds.

Moonshot is also clear-eyed about the nonprofit trap that destroys capacity in our field. Scott’s strategy is “how do I diversify my revenue streams and not be solely reliant on city contracts or grants,” because he refuses to build a team that has to shrink every time a funding cycle ends. He said it plainly: “I don’t want to have to let people go after that grant runs out.”

That is the hidden cost of the legacy model: it teaches organizations to staff up temporarily, then collapse, then staff up again, then collapse again. Founders experience that as inconsistency. Communities experience that as distrust. ESOs experience it as burnout.

So what does Moonshot actually look like on the ground?

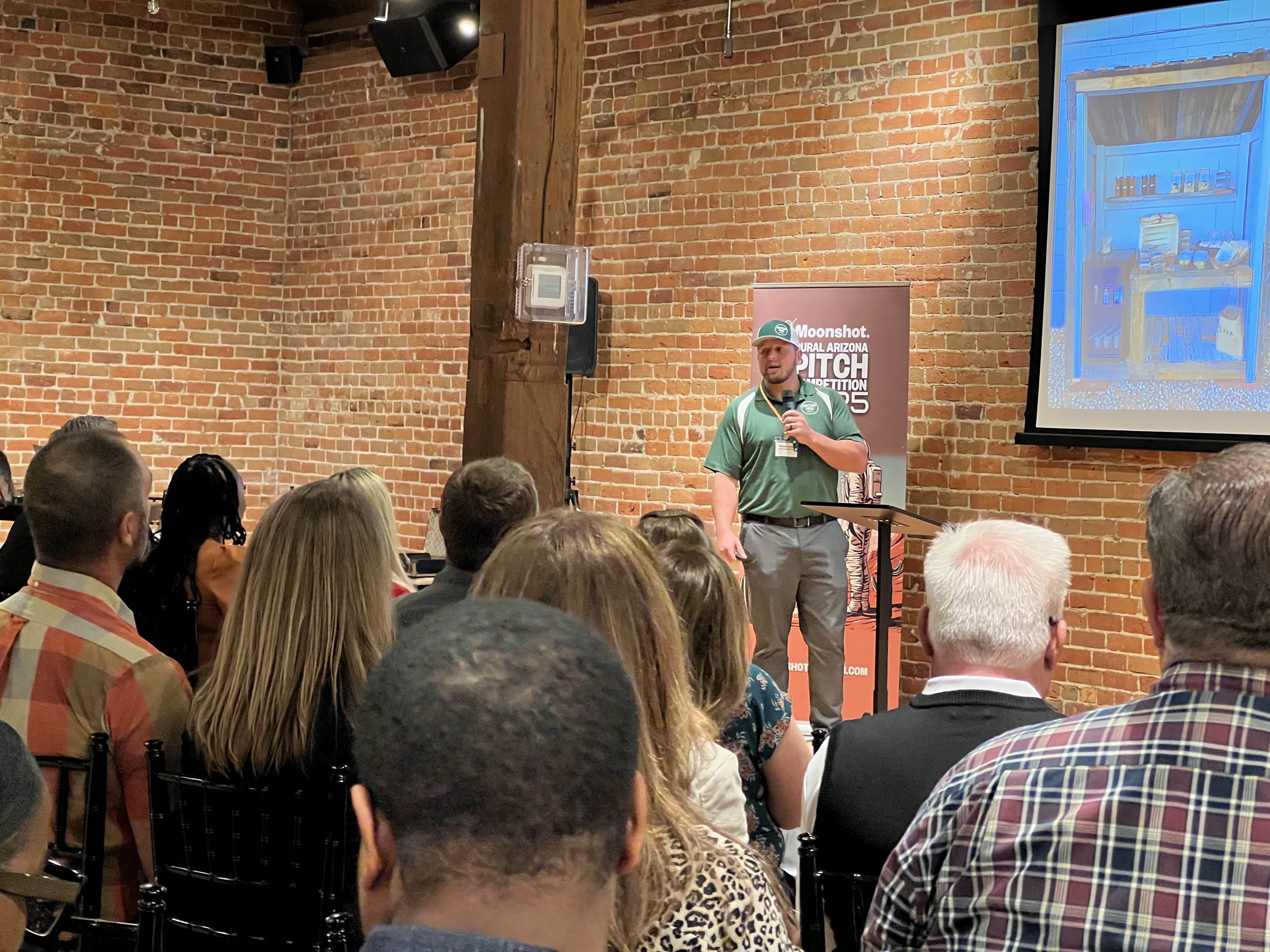

Moonshot’s signature program is the Pitch Tour, and Scott is blunt about what it really is: “We’re a marketing vehicle.” “At the end of the day, I become a game show host,” he says, and you hope you get enough “stickiness” that people buy into their ideas and keep going into the curriculum and the hard work. They bring high production value into towns that are not used to it, and sometimes the audience for finals is five times the number of founders pitching because “this is entertainment in their town.”

And he holds the door open wide. “We welcome as many people into our play pen to help that entrepreneur be successful,” he said, and Moonshot does not try to own the founder’s journey. They want to be “a consistent thing that sits here, that they can take advantage of or tap into when they need to.”

That is what a node does. It provides consistent access to a system larger than itself.

So here’s the story I think Scott and I are telling together:

Local matters, deeply. But local alone is not a strategy for sustainability or scale, especially in rural and midsize markets. If we want founders to have access to broader markets of capital and customers, we need communities to operate together as nodes within the same network, sharing infrastructure, sharing data, and buying into models that are small enough to be “palatable” locally, while still connecting into something that compounds nationally.

The next chasm, Scott says, is capital. Networks make chasms easier to cross. They make delivery possible at lower cost, and they make outcomes legible enough to attract capital.

A small town doesn’t have to choose between going it alone or going without. It can buy five seats, plug into a system, and become part of something bigger than its ZIP code.

That’s not abandoning local.

That’s upgrading local into connected.

To learn more about Moonshot and licensing our services contact info@moonshotaz.com. www.moonshotaz.com

To learn more about Moonshot's Rural AZ Pitch Competition & Tour visit www.moonshotazpitch.com.